Canadians are finally getting cheaper phone plans

There are many things that are more expensive in Canada compared to our peers, but cell phone plans have long been one of them. The United States had unlimited plans years before us, with Canadians waiting until 2019 for the first offerings. While at first glance it may seem that we have at least 6 different providers, the mid tier carriers are actually owned by the larger ones; Fido is owned by Rogers, Koodo is owned by Telus, and Virgin is owned by Bell.

There have been some attempts to introduce new competitors nationally. Wind tried in 2008 to begin offering cheaper plans by focusing on dense urban areas, limiting the amount of towers that they would need to build. This ultimately failed, as the expected ability to share existing cell towers with the big three did not live up to expectations. Wind was acquired by Shaw in 2016, becoming Freedom mobile. Freedom was sold by Rogers to Videotron in 2023[1], and now has settled in as a distant 4th place.

Why phone plans fascinate me

If you have read any other post on this blog, you may be wondering, “what the heck is going on, why are we talking about phone plan prices?”. Well, because they strangely fascinate me. Over the past week I have been thinking about two ideas:

- There are a lot of intricacies in the Canadian context that make our cell phone market unique.

- I have received marketing emails for some truly large gigabyte allowances, and one provider even calls me regularly to try to get me to come back[2]. Something felt off in the market. I wanted to know what the current state of things was.

Canada is different

While we have three main providers, they haven’t spread their cell towers across the country equally according to analysis by Rewheel, a Finnish telecom research firm. This may not come as a surprise for those that have bought home internet, you cannot get home internet via Bell in British Columbia[3], but you can from Telus. In Ontario, it is the reverse. Network sharing agreements are common between the companies, allowing them to build up a substantial moat that new entrants find difficult to overcome. Canadians just experience the new provider as having worse coverage and end up switching back.

Canadians are demanding increasingly more data

In this sense, Canadians probably aren’t unique, but it is interesting to look at the numbers for just how much the demand has increased. From 2017 to 2023, mobile data usage increased by 350%.

Canadian average monthly data usage 2017-2023. Data reported and sourced by the CRTC

| Year | Average Monthly Usage (GB) |

|---|---|

| 2017 | 2 |

| 2018 | 2.5 |

| 2019 | 2.9 |

| 2020 | 3.7 |

| 2021 | 4.7 |

| 2022 | 5.7 |

| 2023 | 7 |

One of the reasons that industry argues phone plans haven’t come down in price (as much as many would like) is because of this increasing demand.

Overall, plans are getting cheaper

When I began researching this topic, I didn’t expect to see that prices were falling by all that much. However, I was surprised to see that prices had fallen quite a bit over the past 5 years, especially for the top tier plans.

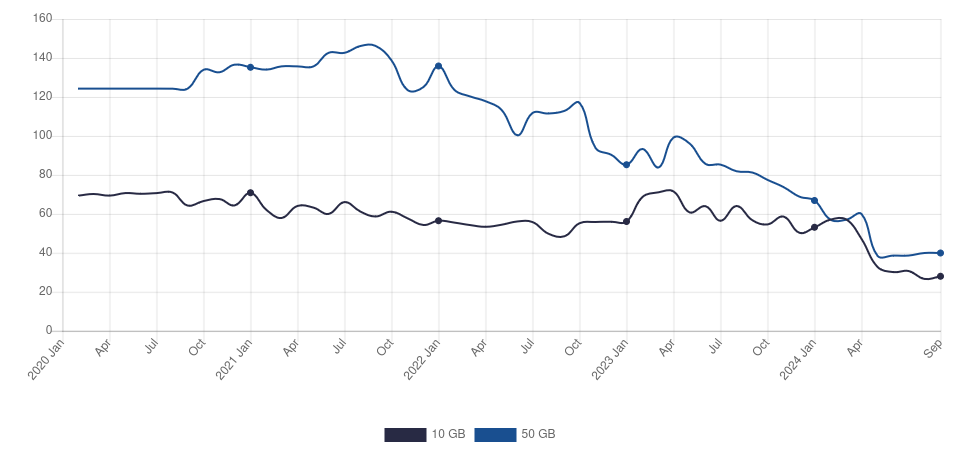

Monthly prices for 10 GB and 50 GB plans (CAD$), 2020 to 2024. Data reported by the CRTC, and shared with permission. Sourced from Statistics Canada.

What’s even more surprising is that this price decrease is more than the United States. From the same report, between 2016 to 2023, prices in Canada dropped almost 40%. In the United States, just 13%.

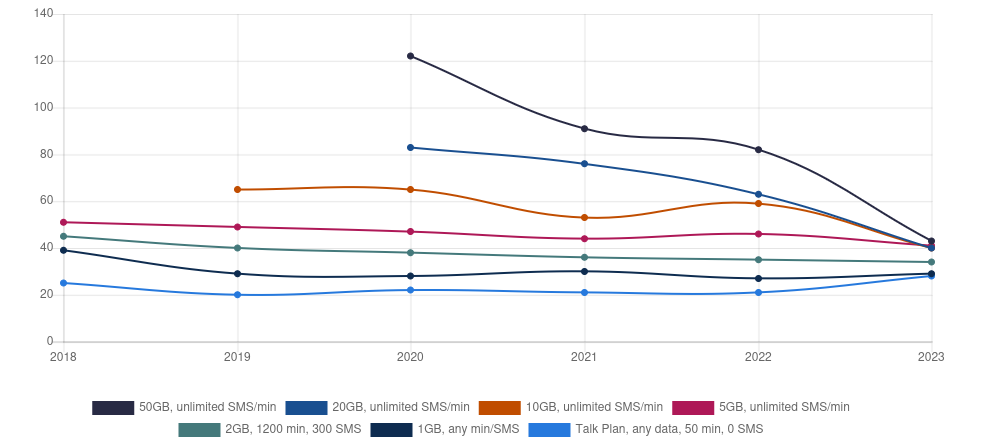

If prices have been falling, why hasn’t this been felt by the average subscriber? I had a hunch because of how the marketing efforts were ramped up, but I haven’t heard any gleeful cheers about how cheap things are. The report has a possible answer to this one as well—while the more expensive plans have become cheaper, the lowest tier plans have roughly stayed the same.

Lowest reported average monthly prices of phone plans dependant on data included in plans. Prices in $CAD. Data reported and sourced by the CRTC, shared with permission

Bandwidth on the modern web

The final question I would like to dig into is whether the web is getting bigger (in terms of the size of pages or data sent to client devices). This would determine whether data usage on plans requires further time to be spent on devices, or whether this usage would increase if customers spent the same amount of time as they currently do, performing similar actions.

For those using the modern web, this won’t come as a surprise; the average data sent per page has increased by 67.2% on mobile between 2021-2025, at least for the thousand most popular websites. This means if users were browsing the same sites, at the same frequency, their data usage would increase by a similar amount without any change of habits.

This was largely driven by a shift to video across multiple platforms. While it is unlikely that bandwidth continues to continue linearly forever, further increases in average page size are likely.

This was done to appease regulators pending an even larger transaction, the merger of Shaw and Rogers. ↩︎

I don’t think I have ever been as actively pursued as I have by this company, I am shocked that they are able to keep the pace up. ↩︎

You could historically get internet from Shaw in British Columbia, which is now Rogers. Confusing I know. ↩︎